‘Otoniel’ is no mere kingpin. He’s a creature of bad US-Colombia policy.

November 15, 2021

Otoniel is one of Thousands of Right-Wing Terrorists whom the Colombian Government Enabled to Fight Communist Rebels with US Weaponry & Intelligence

Last month, the lengthiest manhunt in Colombian history culminated in the capture of the country’s most-wanted criminal, Dairo Antonio Úsuga aka “Otoniel,” head of the notorious crime organization known as Gulf Clan or Urabeños. Colombia's Defense Ministry estimates that this cartel, one of the country’s most powerful criminal organizations, smuggles up to 200 tons of cocaine annually, and has killed over 200 members of Colombia’s security forces.

Otoniel deserves to be brought to justice, but the media’s oversimplified narrative about the takedown of “a drug kingpin” inadvertently serves as free public relations for the United States government’s disastrous foreign policy. The ugly truth is the American and Colombian governments indirectly enabled Otoniel’s rise to power through the decades-long War on Drugs.

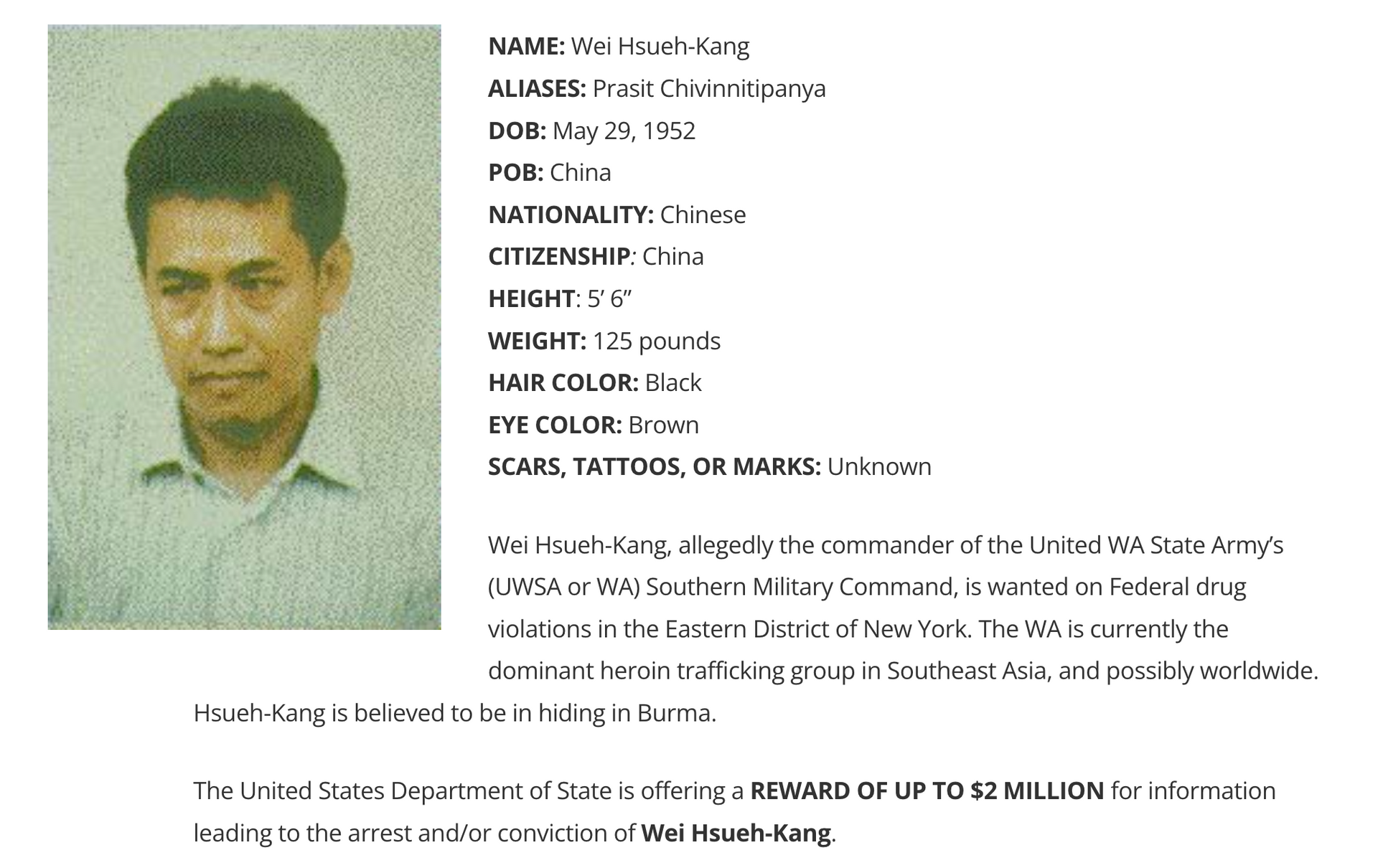

For the last two decades, while U.S. forces occupied the country, Afghanistan has been the epicenter of the world’s opium production with roughly 90% of global supply. After American troops withdrew from the country, and with the Taliban in charge, Afghan opium production drastically declined. There were an estimated 6,200 tons produced in 2022, as opposed to 333 tons in 2023, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). That may surprise some readers as the Taliban have been credibly linked with the heroin trade. The UNODC estimated in 2009 that the Taliban generated $155 million per year from Afghan opium. They weren’t traffickers but they forced traffickers and farmers to pay a “tax” in their territories. Even though those were handsome profits, the Taliban were relatively a minor part of a massive black market worth then roughly $3 billion annually. History shows that the Taliban’s policy on opium has shifted from time to time depending upon their circumstances. An opium ban in Afghanistan seems to fall in line with the Taliban’s tyrannical fundamentalist Islamic modus operandi. However, it also benefits those in power. Several Afghan warlords derive much of their authority as a result from black market profits. Hence, whoever controls the opium trade, or lack thereof, in Afghanistan holds all the cards in a country where the average annual income is 378 US dollars. After the Taliban gained control of Afghanistan in 1996, they struggled to find international recognition. Therefore, the Taliban killed two birds with one stone when its former leader, Mullah Omar, issued an opium ban in July of 2000. That edict was beyond effective. According to UNODC estimates, Afghan opium production dropped from 3,276 tons in 2000 to 185 tons in 2001. The U.S. State Department even approved $43 million of humanitarian assistance for the Afghanistan government just months before 9/11 due to its strong counternarcotics efforts. After 9/11, the Taliban’s power decreased but didn’t cease. America installed a deeply corrupt transitional government. In turn, opium production escalated exponentially. America sided with militias entrenched in the opium trade who opposed the Taliban, such as the Northern Alliance. But, the Western media has only reported in drips and drabs about the U.S.-allied politicians/warlords who have been far more prominently involved in heroin trafficking. The corruption ran to the top. There are too many flagrant examples to list concisely, but notably, a man carrying 183 kilos of heroin was released by the police because he was carrying a signed letter of protection from Afghanistan’s drug czar, General Mohammad Daud Daud. Wikileaks revealed that former President Hamid Karzai once pardoned five police officers who were captured with 124 kilos of heroin. Even Hamid Karzai’s half-brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, was a known drug smuggler who had been on the CIA payroll for years. Practically the entire Karzai administration was on the CIA’s payroll all while the agency knew these officials were drowning in drug money.