Move over Afghanistan, Myanmar is Now the World’s Top Opium Producer

February 5, 2024

With US Troops out of Afghanistan, it is No Longer the Epicenter of Opium Production. Drug Trafficking is Fueling a Civil War in Myanmar.

The U.S. government’s selective counternarcotics enforcement efforts were just as glaring in Afghanistan. To be specific, the Pentagon had an official list of 50 Taliban-linked traffickers who were targeted to be killed or captured. However, the American government used the kid gloves when it helped on the battlefield. Haji Juma Khan was captured in 2001 and almost immediately released. He went on to become a DEA and CIA informant while maintaining his heroin empire. He was eventually arrested by U.S. authorities in 2008 after siding with the Taliban.

Less than a year after the U.S. withdrawal in 2021, the Taliban regained power and their leader, Haibatullah Akhundzada, issued another opium ban in April 2022. Today, we have a situation in which the opium market has shrunk by roughly 95% now that America’s cronies are no longer in power.

Afghanistan police seizing opium

It’d be easy to assume that there’s a grand conspiracy by dirty U.S. government officials to pocket drug money. However, that’s not the case. If we’re going to examine ulterior motives in foreign policy, the $3 billion annual opium black market pales in comparison to the $2.3 trillion that the American government has spent waging war over 20 years in Afghanistan. In other words, the legal racket from the military industrial complex is far more lucrative than the drug game.

In many ways, America doesn’t wage a “war on drugs,” instead it selectively enforces these laws where it advances its interests. In other words, a corrupt foreign world leader can enjoy a fruitful relationship with the American government if he aligns with America’s economic and military agenda. Think of Panamanian strongman, Manuel Noriega. He was on the CIA’s payroll for years despite a well-known link with drug cartels. However, as his allegiances shifted, he became persona non grata in DC which eventually led to the Panama invasion of 1989.

Last month, the UNODC announced that Myanmar became the world’s top opium producer. It’s not shocking news. Myanmar had long been the 2nd largest producer; albeit, a far distant second place. Keep in mind, this country was already one of the main global manufacturing hubs of methamphetamine. It’s also not shocking because the U.S. government has long played a role in the black markets of Myanmar.

Not long after Burma (present-day Myanmar) declared independence from Britain in 1948, it became embroiled as a proxy in the Cold War. (The Burmese military junta changed their country’s name to Myanmar in 1989 and the U.S. government has never recognized the new name.)

The communist dictator, Mao Zedong, began his revolution in China in 1949. That pushed the former Chinese leader, Chiang Kai-shek, out of power. Chiang Kai-shek fled mainland China to Taiwan and his nationalist party, Kuomintang (KMT), ruled the island with an iron fist.

Several KMT troops also crossed the border into Burma. Their original intention wasn’t to take over Burma. Rather, they wanted to use the country as staging grounds for future operations to overthrow the Mao government. The KMT migrated to a region in Burma (Shan State) that lacked development/infrastructure and opium was the main cash crop. The KMT heavily taxed these farmers, which indirectly forced them to produce much more product to make the same income.

President Truman authorized a secret mission, “Operation Paper” in 1950 in hopes of overthrowing Mao by having the CIA arm and train the KMT. There were several incursions into China by the KMT but no real success. The KMT couldn’t point to many results on the battlefield, but the support it received from U.S. intelligence facilitated a massive increase in opium in the region. There were roughly 30 tons of opium produced in 1950, which increased to over 300 tons by the mid-1950s.

Keep in mind, none of this activity was authorized by Congress. Hence, the KMT’s drug money helped to keep their group operational. The KMT never felt a moral obligation to hide their connection to drug trafficking. The KMT General, Tuan Shi-wen, told a reporter, “Necessity knows no law. That is why we deal with opium. We have to continue to fight the evil of communism. To fight, you must have an army. An army must have guns. To buy guns, you must have money. And in these mountains? The only money is opium.”

Alfred W. McCoy, history professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, is the foremost resource on this topic. During the Vietnam War, there were numerous reports of how the Golden Triangle (Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos) had become the opium production center of the world and notable U.S. allies were involved. However, when McCoy published The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade in 1972 it put the pieces of the puzzle together and exposed how our government brazenly enabled traffickers in the Golden Triangle in hopes of crushing communism.

For Myanmar’s entire history, there have been large regions that are essentially ungoverned and lack economic development/infrastructure. These regions have been ruled by armed non-state actor groups, many of which are largely funded by criminal proceeds. Both U.S. intelligence and the Myanmar government have tried to foster loyalty by enabling this criminality. However, both sides have miscalculated that they could buy loyalty from these narco warlords.

The Burmese dictator, U Ne Win, made a businesslike decision in 1963 to allow militia groups to traffic opium as long as operated as defense groups against rebel factions. However, these ostensibly pro-government forces, known as Ka Kwe Ye (KKY) (which means “defense” in Burmese) did very little to protect the Burmese junta’s interests, and the program was disbanded ten years later.

A couple of the world’s most notorious drug kingpins, Khun Sa and Lo Hsing-han, were part of this KKY program. Both of them got their start within the KMT and managed to maintain off/and/on relationships with both the Myanmar government and foreign intelligence. Khun Sa, “King of the Golden Triangle,” at one point had a 20,000-member private army, that controlled 80% of Myanmar's opium production and approximately half of the world's supply. He eventually agreed to a truce with the Myanmar government in 1996 and gained safe haven.

Lo Hsing-han enjoyed an even lengthier criminal reign. One year after Khun Sa retirement from drug trafficking, the U.S. government publicly criticized Myanmar’s government for empowering Lo Hsing-han. One State Department official said, “Since 1988, some 15 percent of foreign investment in Burma and over half of that from Singapore has been tied to the family of narco-trafficker Lo Hsing Han.”

What the State Department failed to mention was that their organization and the CIA went to extraordinary lengths to protect Lo Hsing-han. A few years earlier, the State Department and CIA successfully pressured the DEA to transfer their most tenured agent in Myanmar, Richard Horn, for simply doing his job too well.

Richard Horn’s phone conversations were illegally recorded by the CIA. Horn had communications with an informant, U Saw Lu, a community leader in the autonomous Wa State. U Saw Lu was a local anti-narcotics official and he notified Horn about a senior Myanmar intelligence official who protected Lo Hsing-han’s drug shipments. Horn and U Saw Lu were also in the preliminary stages of seeking international assistance to create an opium crop substitution/eradication program in the Wa State.

The CIA’s station chief in Myanmar, Arthur Brown, spiked this initiative by leaking a U Saw Lu-signed document about this plan to a Myanmar intelligence official. That decision put U Saw Lu in serious danger. Myanmar’s junta had previously nearly tortured him to death. He was hung upside down for 56 days, beaten with chains, given electric shocks to the groin, and had urine repeatedly poured on his face.

Richard Horn sued the two CIA officials in 1994 for violating his civil rights. A 15-year legal battle ensued and the CIA agreed to a $3 million settlement. In that same year the Myanmar government formed a program, Border Guard Force (BGF), which was similar to the Ka Kwe Ye (KKY) program of 1963. Myanmar attempted to assuage the several ethnic armed organizations that refused to agree to a ceasefire. These groups were allowed to become a Border Guard Force (BGF) and receive income from the government to protect their territory.

This was a formalization of a decades-old informal policy. Since the coup of 1962, Myanmar’s army, known as the Tatmadaw, has essentially played a game of wack-a-mole with the country’s ethnic rebel groups. Currently, there are 21 ethnic armed organizations controlling large portions of the country and it’s an impossible task to militarily defeat them all. Therefore, Myanmar’s leaders have found the carrot to be a more effective counterinsurgency strategy than the stick. In other words, these Border Guard Forces (BGF) engage in criminal activity, with little to no interference, as long as they aren’t openly hostile to the government.

The United Wa State Army (UWSA) is the largest ethnic armed organization in Myanmar. Their organization agreed to a ceasefire in 1989. That neutrality helped enable this group to become arguably the second most powerful non-state actor (behind Hezbollah in Lebanon) in the world with as many as 30,000 soldiers. The U.S. Treasury Department once labeled the UWSA as “the largest and most powerful drug trafficking organization in Southeast Asia.”

United Wa State Army (UWSA) (Wa State TV)

Again, the criminal lifestyle is also cozy for the junta’s BGFs. The Kokang BGF, for instance, oversees a region rife with drug trafficking and illegal gambling. That’s not to mention the cyber scams that are run by human trafficking victims. The UN has estimated that as many as 100,000 victims (primarily from China) have been lured to Myanmar to work in these fraud centers. That’s not even counting the number of victims to their scams. If these human trafficking victims don’t meet their quotas, they’re tortured and, in some cases, murdered. It should be no surprise that the profits from such brazen depravity lead directly back to the Myanmar junta’s highest levels.

The drug money corruption also goes all the way to the top of this narco dictatorship. For example, during a drug and arms trafficking in Bangkok, Thai officials found records linking Myanmar’s de facto leader, Min Aung Hlaing. Title deeds and banks of his daughter and son were found at the home of the trafficker.

As mentioned earlier, Myanmar now has the highest opium production in the world. However, the timing of this frenzied drug trafficking coincides with the military coup that took place three years ago on February 1, 2021. The coup removed a quasi-democratic government that had been in place since 2010. A civil war ensued and continues to this day. Over 6,000 civilians have been killed, along with 1.5 million displaced.

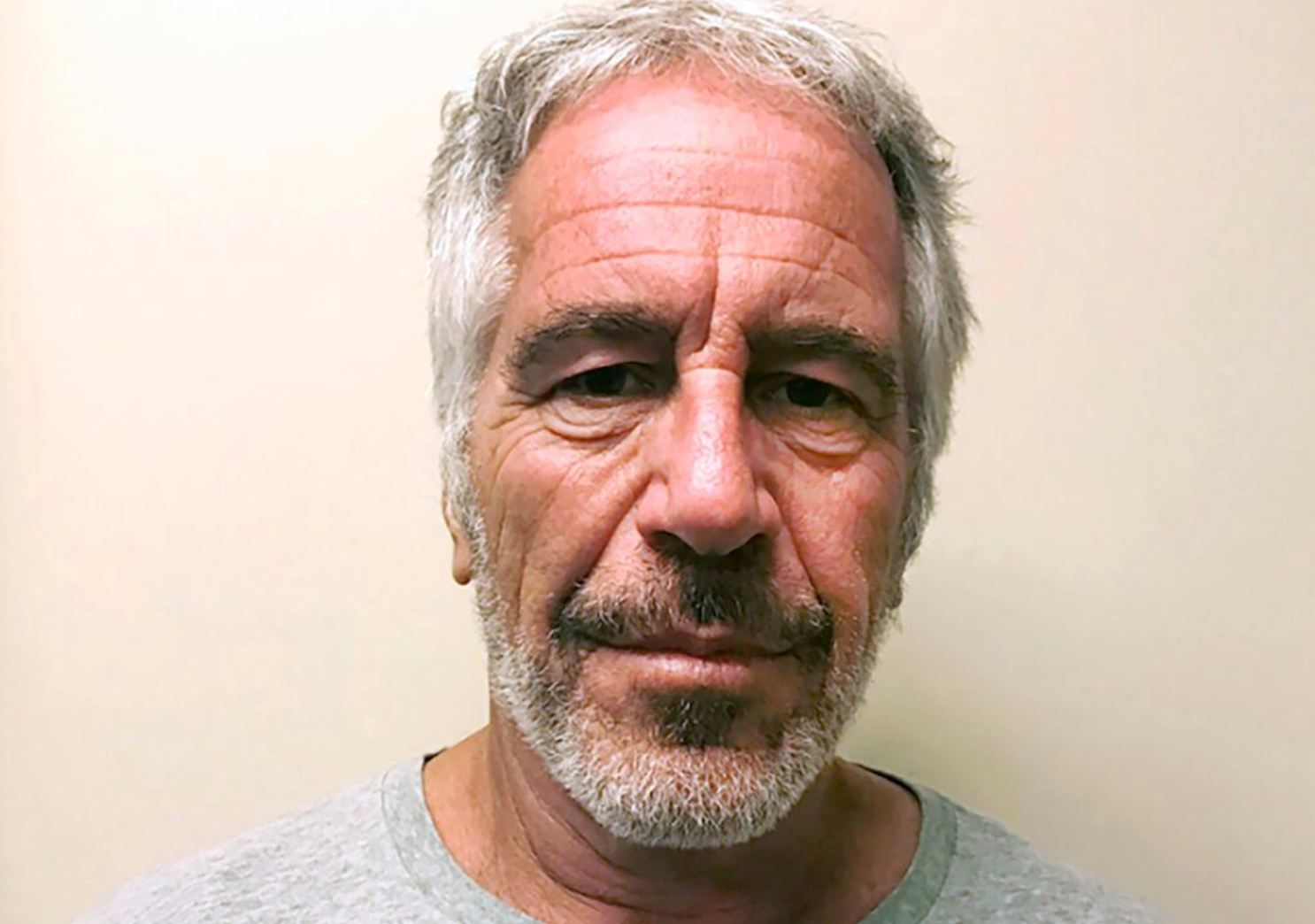

Min Aung Hlaing (de facto leader of Myanmar) (Wikipedia)

Myanmar’s junta is rapidly losing territory and soldiers now that some of the rebel groups are fighting in an aligned front. This momentum shift peaked on October 27, 2023 with Operation 1027. This was a joint military operation waged by the Three Brotherhood Alliance, primarily composed of three ethnic armed organizations, the Arakan Army (AA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA).

After facing numerous humiliating military defeats, and losing over 130 military posts, Myanmar’s de facto leader, Min Aung Hlaing, made a declaration that gained several international headlines. He stated that the rebels are funded with drug money.

In particular, he pointed to the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). These allegations are true. The MNDAA has a long history connected with the drug trade, although the organization has made some strides to cut back on this type of activity in its region. Likewise, the Arakan Army (AA), Karen National Liberation Army, and other rebel groups are linked to drug money. However, not all of these rebels are complicit in this trade. The Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) enforces a strict anti-drug policy in its territory.

All in all, this is a complex issue in one of the most lawless countries in the world, but what is clear is how the U.S. government, along with Myanmar, isn’t truly fighting a war on drugs. They’re using the war on drugs as a pretext to advance their interests. Decades ago, then-Burma had a serious drug problem, but the U.S. intelligence agencies dumped gasoline on the flames. And now, our American officials root for the narco rebels to defeat the narco regime so that a semi-democratic state can be restored in Myanmar.