Did a Narco-Linked Former Haitian Leader Have President Moïse Assassinated? (Part II)

March 19, 2022

Former Haitian President Michel Martelly Has Links with the Suspected Assassins

(Left to Right) Former President Michel Martelly (Wikipedia), Former President Jovenel Moïse (Twitter), Current President Ariel Henry (Wikipedia)

It's clear from Moïse’s track record in office that he was anything but an anti-corruption crusader. Hence, Moïse’s sudden penchant for prosecuting drug traffickers seemed like a decision to eliminate his rivals and stay in power. He had a horrific human rights record, was tied to a massive embezzlement scandal, and overstayed his constitutional mandate.

Moïse ordered the investigation of Charles “Kiko” Saint-Rémy, the brother-in-law of former President Martelly. Haitian authorities scrutinized the records of his connection with the eel industry for evidence of money laundering. Saint-Rémy was an influential advisor for Martelly and served in his cabinet. He even intervened to help have the charges dropped against a close friend of Martelly, Woodly Etheart, who was arrested in 2015 as the reported leader of the Galil Gang. That kidnapping syndicate allegedly amassed nearly $2 million in ramsons.

Woodly Etheart (Haiti National Police)

The DEA has investigated Charles “Kiko” Saint-Rémy for years, particularly a high-profile drug bust in 2015 in Port-au-Prince. A company owned by one of Haiti’s wealthiest businessmen, Marc Antoine Acra, received a freight shipment of sugar from Colombia aboard the Manzanares MV. During the offloading, one of the packages burst open and revealed that the ship was loaded with illegal drugs. A mad scramble ensued before the DEA and U.S. Coast Guard arrived.

Charles "Kiko" Saint-Remy (Twitter)

Keith McNichols, a former DEA agent, said that Dimitri Hérard (Moïse assassination suspect) led a group of Haitian police officers who grabbed the drugs and fled the scene. An estimated 800 kilos of cocaine and 300 kilos of heroin (a combined $100 million street value) were on board that ship, but only about 11% of the contraband was actually brought into evidence. Dimitri Then-President Michel Martelly shielded Hérard from investigators and later recommended for him to become Moïse’s head of security. Marc Antoine Acra was appointed as an ambassador months later.

Only one person, a low-level operator, was prosecuted in the Manzanares MV case. American media outlets referred repeatedly to this as a “bungled” investigation as though the DEA agents involved were a bunch of Keystone cops. However, what happened is that high-level U.S. government officials interfered in the investigation to protect a small group of powerful Haitians.

Former DEA agents, Keith McNichols and George Greco, blew the whistle about institutional efforts to bury the truth. Remarkably, a Haitian investigator was paid by a DEA official with $1,500 of U.S. taxpayer money to destroy the confiscated drugs. The whistleblowers also reported internally that a senior DEA official received $1.2 million in “irregular expenses.” That same official met privately with Charles “Kiko” Saint-Rémy on multiple occasions. That was a violation of DEA policy. Their members are barred from private meetings with trafficking suspects because it leaves room for corruption.

Just to reiterate, Haiti is a major drug trafficking corridor and the President’s brother-in-law/advisor met privately with a DEA official who potentially accepted as much as $1.2 million in bribes. You can read between the lines.

You can also tell a lot about an organization by how it handles a crisis. Does it root out corruption or punish the messenger? In this case, the government official involved in backroom conversations never faced any consequences. In contrast, Keith McNichols and George Greco didn’t receive their government-mandated whistleblower protections. They both resigned from the agency after facing continual retribution for simply reporting potential fraud, waste, or abuse.

If it sounds inconceivable that the American government would safeguard a Haitian drug kingpin for political reasons, there is plenty of historical data that tells otherwise. The DEA’s most high-profile whistleblower, Michael Levine, told an investigative reporter in 1993 that what has then happening in Haiti was “just another example of elements of the U.S. government protecting killers, drug dealers and dictators for the sake of some political end…I saw the drug traffickers take over the government of Bolivia in 1980, ironically with the assistance of the CIA, and we (the DEA) just packed up our office and went home.”

What happened in Bolivia was informally labeled the “Cocaine Coup.” The CIA supported the removal of Bolivia’s President Hernan Siles Zuazo, a democratically-elected leader and moderate leftist. Gen. Luis Garcia Meza led the brutal right-wing military dictatorship and his regime’s enforcers included U.S. intelligence assets, such as Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie.

Bolivian cocaine production and trafficking increased substantially. The drug lord, Roberto Suárez, was an integral part of this junta and the corruption was ubiquitous. Yet, Michael Levine’s efforts to arrest Suárez and other Bolivian kingpins were suppressed by high-level DEA officials. Levine faced tremendous retribution within the DEA for trying to take down major trafficking networks in Bolivia tied to U.S. intelligence and he wrote about this mind-boggling hypocrisy in The Big White Lie: The Deep Cover Operation That Exposed the CIA Sabotage of the Drug War. The key takeaway is that the DEA plays second fiddle to the CIA.

The Bolivian “Cocaine Coup” was similar to the coup in Haiti in 1991. Even though Haiti declared its independence in 1804, their country’s first free and fair election didn’t take place until 1990. It’s impossible to concisely summarize the U.S. government’s anti-democratic practices in Haiti over the last two centuries, but here are a few highlights. The CIA supported a coup that led to the brutal “Papa Doc” Francois Duvalier dictatorship (1957-1971). As many as 50,000 citizens were killed by his regime. The CIA also equipped/trained the enforcers of his son’s dictatorship, “Baby Doc” Jean-Claude Duvalier (1971-1986).

Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier (standing) and Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier (seated) - Wikipedia

A CIA-backed general, Henri Namphy, overthrew “Baby Doc” Duvalier. Namphy was heavily involved in narcotics, but he never faced charges. Namphy, like other Haitian military junta leaders who took power after Baby Doc’s demise, were all well-received by the U.S. power structure.

The elite Haitian bourgeoisie and several American leaders felt threatened by an influential preacher, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who eventually became Haiti’s first democratically-elected president. He practiced what is known as liberation theology, which essentially combines religion and social justice. For popularizing such beliefs, he faced multiple attempts on his life.

Former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide - Wikipedia

The most notable example was the St. Jean Bosco Massacre. Aristide was able to escape the St. Jean Bosco church on September 11, 1988, but 13 people were killed and another 77 were injured. Franck Romain, who was then the Mayor of Port-au-Prince, ordered the attack. Romain had trained many years earlier in the U.S. at the notorious School of the Americas and had led Papa Doc’s notorious enforcer unit, the Tonton Macoutes.

Tonton Macoute - (Images from Latinamericanstudies.org and Twitter)

Nonetheless, the U.S. media shielded the human rights abuses in Haiti. One week after that massacre, The New York Times published a puff piece for Haiti’s military dictator, Prosper Avril. It provided this vignette, “Despite his staunch support for the Duvalier dictatorship, General Avril has no reputation for cruelty.” Prosper Avril is a perfect example of a Haitian narco dictator who the U.S. government safeguarded. Testimony from a U.S. Senate Subcommittee directly named Prosper as a significant facilitator for Colombian cartels, yet he never faced charges and even lived in the U.S. for years after leaving power in Haiti.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide was viewed as a man of the people and won a decisive victory in December 1990 over the CIA’s favored candidate. The Senate Intelligence Committee demanded to know which Haitian candidates the CIA financed, but CIA officials refused to give names. The Senate Intelligence Committee responded by cutting off funds for this program. However, records show that the CIA’s cut-out organization, the National Endowment for Democracy, provided Marc L. Bazin (a former World Bank official) with $36 million.

Aristide served less than a year in office before a paid-informant of the CIA, Haitian Gen. Raoul Cedras, led a coup against him. This de facto regime was directed by members of a Haitian intelligence unit (SIN) that had been armed/trained by the CIA. SIN was ironically supposed to be an anti-narcotics unit, but that group turned the island into one of the world’s biggest drug transshipment points after Aristide’s ouster.

Another graduate of the School of the Americas, Lt. Col. Joseph-Michel François, acted as the regime’s enforcer. He was nicknamed “Sweet Micky” reportedly because he smiled widely as his forces issued widescale violence against anti-coup protestors. Michel Martelly, the future president of Haiti, who was then a nightclub owner and singer, shared the same nickname. Martelly’s nightclub, “The Garage,” regularly catered to the post-Duvalier regime’s military leaders. At a time of high animosity toward the government, Martelly played compas, which was the only genre allowed during the Duvalier dictatorships. Michel Martelly was admittedly a member of the Tonton Macoutes in his youth and he was friends with Joseph-Michel François, so much so that Joseph-Michel François reportedly gave him the nickname.

Long after he was of use for imperialist purposes, American authorities arrested Joseph-Michel François in 1997 for trafficking 33 tons of cocaine and heroin. However, the red flags were visible from the early days of the junta. The DEA’s station chief in Haiti, Tony Greco, had to flee the country for his safety. After a successful drug bust, he received a death threat on his private telephone line that only Raoul Cedras and Joseph-Michel François possessed.

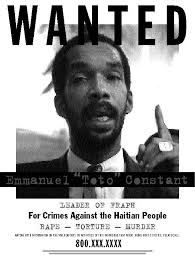

Many of the political murders were also committed by the Haitian paramilitary group, FRAPH, which was aided and financed by the CIA. The CIA’s director, James Woolsey, later said, “The worse the group, the more we are likely to want to collect intelligence from them…Human-rights violations make a group of more interest to us.” The Haitian government subsequently convicted the leader of FRAPH, Emmanuel Constant, for murder.

Constant was convicted in absentia because the U.S. government safeguarded him on American soil. You may be asking, “How’s that possible?” Congress passed the 100 Persons Act which allows the CIA to provide legal immigration status to 100 individuals per year for “national security” reasons even though this distinction is often given to war criminals like Emmanuel Constant. Ironically, Constant was not held accountable by U.S. law enforcement for his crimes in Haiti. Instead, he was arrested for mortgage fraud committed in New York in 2006.

(Left to Right) General Raoul Cedras and Lt. Col. Joseph-Michel François, FRAPH leader Emmanuel Constant (Images PBS, Alchetron, SOA Watch)

An estimated 4,000 people were killed by the post-coup Haitian government, along with thousands more tortured during the three-year reign of terror. Despite American complicity in the coup, the U.S. government showed no humanitarian sympathy for the people of Haiti. As many as 34,000 Haitian refugees were denied entry and held at U.S. naval base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

The Clinton administration eventually negotiated to have Aristide return to office in October 1994. The U.S. military mission was named “Operation Uphold Democracy.” Despite the sanctimonious nature of this mission, the U.S. didn’t allow Aristide to return unless he agreed to a few conditions from the IMF and World Bank.

Conversely, the Clinton administration offered remarkably cushy terms for Haiti’s narco leaders. Raoul Cedras lives in Panama in the lap of luxury. He and his right-hand man, Gen. Philippe Biamby, were able to have the $79 million in U.S. accounts unfrozen as well. Gen. Biamby, along with 23 members of his and Cedras’s family, were allowed to move to America. The U.S. government even agreed to pay rent to Cedras for his multiple properties in Haiti. “(This) was something (Cedras) felt strongly about, and it wasn't something we were going to allow to disrupt his departure,” said White House spokeswoman Dee Dee Myers.

Aristide had been removed from power for three years, but he still abided by the strictest interpretation of the Constitution by leaving office in February 1996. That’s an important distinction as President Jovenel Moïse tried to overstay his term for another year because his entry into office was delayed by a year.

As mentioned earlier, the Haitian Constitution bans a president from serving consecutive terms. René Préval served as Aristide’s placeholder just like how Moïse was thought to be Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly’s placeholder. Aristide was elected again in 2001, but the early warning signs of the next coup were evident.

Part I of this series described the outlandish control over Haiti held by the Core Group, a shadowy group of ambassadors from Germany, Brazil, Canada, Spain, the U.S., France, the European Union, along with representatives from the U.N. and the Organization of American States (OAS). The early stages of this coup were held in the 2003 “Ottawa Initiative on Haiti” meeting in which U.S., French, OAS, and Canadian officials discussed overthrowing Aristide and placing the country under U.N. control.

French leaders were motivated to see Aristide go as he had demanded $21.7 billion in reparations. In 1804 Haiti gained independence by defeating the French military to become the first country founded by former slaves. However, the French king later demanded “indemnity” payments to guarantee their freedom because the French viewed this revolution as a loss of property. The Haitian government settled upon a payment of 90 million francs ($21 billion in current value), which was several times the country’s GDP. These indemnity payments to French and U.S. banks crushed Hait’s prosperity and saddled the country with a form of debt slavery that lasted until 1947.

Aristide’s demand was not unjustified. And this idea had widespread support. However, his detractors in Haiti were gaining steam. As Part I of this series detailed, Ariel Henry, the current de facto leader of Haiti, was then an opposition leader of the Democratic Convergence that called for overthrowing former President Aristide. He received funding from the CIA-linked International Republican Institute. Henry later became part of the “Council of Sages,” a group that held de facto power over the country after the coup.

The coup began on Feb 5, 2004. George W. Bush sent U.S. troops to Haiti a few weeks later to “protect the U.S. embassy” in Port-au-Prince. This attack was led by U.S.-trained paramilitary leaders who crossed the border from the Dominican Republic where they organized the coup. The top commanders were Guy Philippe who was heavily involved in drug trafficking, Jodel Chamberlain (FRAPH leader), and Gilbert Dragon who was part of the Moïse assassination. This group was also reportedly funded, in part, by “Sweet Micky” Joseph-Michel François. He fled to Honduras where government officials refused to accept extradition requests for him to face drug charges in the U.S.

(Left to Right) Guy Philippe, Jodel Chamberlain, and Gilbert Dragon (Images - Indybay, Alchetron, Latinamericanstudies.org)

Despite the junta’s obvious ties to drug trafficking, American leaders tried to use the “War on Drugs” as a pretext for overthrowing Aristide. Earlier that morning, news reports quoted anonymous U.S. officials alleging that they’ve witnessed “uniformed Haitian police unloading planeloads of cocaine for traffickers” and that the corruption reaches “the highest levels of the government.”

Later that evening on February 28, 2004, the U.S. military surrounded the presidential palace and forced Aristide to leave the country. According to Aristide, he was told that the rebels would soon be at the presidential palace and the U.S. would not protect him. He, along with thousands of Haitians would be killed, if he didn’t resign. Aristide was then brought to the airport where he was flown to the Central African Republic (CAR) under the supervised custody of President François Bozizé who gained power a year earlier in a coup.

Ironically, it was Luis Moreno from the U.S. embassy, a former “drug warrior,” who accepted Aristide’s “resignation.” That led to another era that was similar to the “cocaine coup” of 1991. The post-2004 military junta inflicted rampant violence on the population with as many as 3,000 Aristide supporters being killed.

U.S. troops patrol Haiti during the 2004 "peacekeeping mission" (Image - Latinamericanstudies.org)

Aristide’s administration was filled with corrupt officials who enabled drug trafficking, but there’s no compelling evidence that Aristide was involved. For instance, his former head of security, Oriel Jean, was captured in Canada and extradited to the U.S. after fleeing the country. Oriel Jean had accepted lucrative bribes from drug traffickers. U.S. prosecutors offered him a sweetheart plea deal in which would serve no time in prison, get a new identity, witness protection, and money in exchange for testimony against Aristide. Jean testified against various Haitian officials to have his sentence reduced to three years in prison, but he never implicated Aristide.

The 2004 coup installed Interim Prime Minister Gerard Latortue who had been in the U.S. for the last 16 years. He was a former World Bank and IMF official. Gerard’s cousin is Senator Youri Latortue, an ally of former President Michel Martelly. A Wikileaks cable described as Youri Latortue someone who “may well be the most brazenly corrupt of leading Haitian politicians” and deeply involved in drug trafficking.

A few years later, the Core Group intervened in the 2010 election. Ricardo Seitenfus, the former Organization of American States (OAS) special representative to Haiti, acknowledged that the Core Group “decided who the next president of Haiti would be before the elections even took place.” Their favored candidate was Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly. At that time, Martelly had never held public office and was the country’s most popular musician. That background allowed Martelly to craft an image of a rebellious outsider. However, the more accurate label would have been a puppet for foreign interests entrenched in Duvalierism.

Michel "Sweet Mickey" Martelly (Facebook)

The Core Group created an “electoral coup” in Haiti. Martelly came in third place in the first round of the election, which meant he wouldn’t have been eligible for the mandated runoff election for the two finalists. However, the head of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), which was established after the 2004 coup, threatened to remove President Préval from the country just like Aristide if Martelly wasn’t included in the runoff election.

Préval didn’t back down. Then the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N., Susan Rice, threatened to cut off foreign aid to Haiti. Likewise, Hillary Clinton, then serving as Secretary of State, traveled to Haiti to meet with President Préval. The pressure from Hillary Clinton propelled Martelly into the runoff election and the candidate from Aristide’s party was removed. That international support, along with financial assistance from U.S. aid organizations, helped guide Martelly into the presidential palace.

Martelly, a long-time Miami resident and son of a Shell Oil executive, made it one of his first orders of business, before he officially became President, to travel to Washington D.C. to meet with Hillary Clinton and World Bank and IMF officials. Martelly’s administration was riddled with corruption, but his international supporters carried water for him no matter the circumstance. That included scandals for him receiving roughly $2.5 million in kickbacks for handing out lucrative government contracts. Also, one of his advisors was arrested for murder and released months later. There hadn’t been a parliamentary election since 2010, which allowed Martelly to rule by decree, yet the Core Group said that it would “trust that the Executive…will act with responsibility and restraint.”

Martelly’s connections with drug trafficking were evident before the Manzanares MV case. One of Martelly’s friends and major campaign donors was arrested for drug trafficking under strange circumstances in 2013. Evinx Daniel was a wealthy businessman and owner of a beachfront hotel that Martelly frequented. Evinx Daniel claimed that the 23 packages of marijuana on his yacht had been discovered floating in the ocean. His friend, Charles “Kiko” Saint-Rémy (Martelly’s brother-in-law) notified the DEA about the drugs before landing ashore so that the drugs could be handed over to the authorities.

The prosecutor, Jean Marie Saloman, didn’t believe Daniel’s good Samaritan act. Saloman arrested him as he likely notified the authorities to preempt against a larger drug conspiracy charge. The Justice Minister intervened, and Daniel was released the next day. Saloman was suspended from his position afterward and needed to flee the country.

Michel Martelly then visited Daniel’s beachfront hotel and stayed overnight. It seemed to be an odd sign of support from a sitting president to visit a suspected drug trafficker’s place of business so soon after a highly-visible arrest. However, that visit may have had been made for another reason, something similar to a fishing trip with Fredo. Three months after the arrest, Daniel went missing. The police later found a burnt body that is unofficially believed to be Evinx Daniel. The last person to have seen him alive was Jovenel Moïse, a former business partner of Daniel.

As mentioned earlier, Maria Abi-Habib’s investigation pointed out that Charles “Kiko” Saint-Rémy helped to have the kidnapping charges dropped in 2015 against Martelly’s close associate, Woodly Ethéart. The charges were subsequently re-issued by a judge in 2018, but he never went into custody. Ethéart was a fugitive, but he had remained in the open in the affluent areas of Port-Au-Prince over the years. However, Ethéart was seen taking pictures with Michel Martelly before his concert in the Dominican Republic in May 2021. That led to his arrest by Dominican authorities. He was extradited to Haiti to face charges of kidnapping, money laundering, and drug trafficking.

According to Maria Abi-Habib’s sources, Moïse was thrilled when finding out about Ethéart’s arrest. And he refused to accept numerous phone calls from Martelly and Saint-Rémy on Ethéart’s behalf. Moïse’s son, Joverlein, agreed that the arrest could have been the motivation behind the murder. He said, “It is possible that Martelly saw that arrest as some kind of disrespect, that my father was a traitor and was betraying the Martelly family.”

Conclusion

Moïse’s assassination doesn’t fall within the customary pattern of U.S.-sponsored coups. Typically, the national security establishment favors regime change when there’s a leftist reformer who opposes American economic and military interests. However, Moïse’s resume was more like the type of right-wing, puppet authoritarian leader who is installed after a U.S.-supported coup.

Moïse supported the U.S. geopolitical agenda. He recognized Juan Guaidó as the president of Venezuela. That was a provocative move considering that Venezuela’s Petrocaribe program provided Haiti with billions of dollars of subsidized oil. Ironically, Moïse’s companies were implicated in a smaller part of an overall $2 billion embezzlement scandal of Petrocaribe funds.

On a similar note, with a fiscal crisis in place, he followed the neocon blueprint of seeking IMF loans and implementing austerity measures. A series of deadly protests followed after Moïse obliged the IMF’s demand that oil subsidies were removed. That raised the price of gas to $4.60 per gallon in a country where 78% of the population lives on an income of less than $2 per day.

He also employed what were essentially right-wing death squads. That kind of draconian force was meant to prevent any kind of populist uprising. There were multiple massacres committed in poor, left-leaning areas in which police/gangs torched entire neighborhoods, tortured people, committed acts of sexual violence, and killed people en masse.

However, Moïse didn’t stay within his role. As mentioned earlier, Moïse was viewed as the placeholder for Martelly’s next term. The media dubbed him the “Banana Man” because he was an unknown political entity who had a banana exporting business. Oddly enough, Moïse’s lack of political background may have cost him his life as he seemed to truly take America’s “War on Drugs” at face value. What he apparently didn’t know is that the American government often aligns with narco political leaders as long as such leaders advance the U.S. geopolitical agenda.

Moïse was essentially a puppet of a puppet. Better said, he was a puppet until he wasn’t. According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, multiple sources close to Moïse said that he didn’t plan to support Martelly in an upcoming election. Moïse’s term was supposed to end on February 7, 2021, but he didn’t plan on leaving office until February 7, 2022. And Moïse, at times, alluded that he may be changing the Constitution and staying longer.

On February 7th, a government raid arrested 18 people, including a sitting Supreme Court judge, a high-level police inspector, and a former government minister. They were accused of fomenting a coup against him. Two days later, he fired three Supreme Court justices. Those were the telltale signs of someone who was looking to consolidate power.

When The New York Times buried the lede, it did not provide the appropriate context for its investigation, “Haiti’s Leader Kept a List of Drug Traffickers. His Assassins Came for It.” The drug trafficking angle is a red herring that helps to avoid asking the question of whether the former president of Haiti was involved in Moïse’s assassination. In no way was there definitive proof, but it presented strong circumstantial evidence. With that said, Martelly may eventually cruise to an easy victory next year and return to the presidential palace.

The aspect that every American citizen needs to ask is whether our government was involved. There’s plenty of evidence to suggest so, but like the case against Martelly, it’s far from conclusive as well. Unfortunately, Haiti’s history shows that the true intellectual authors behind this crime won’t be held accountable unless the masses dig deeper for the truth.